Circles

Circles are strong, so my engineering husband tells me. The more I see of this country, the more I agree with him. I see evidence of their strength everywhere.

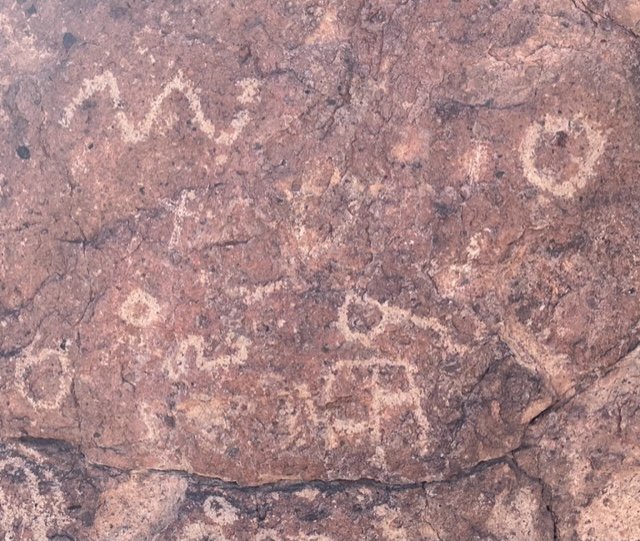

In petroglyphs, circles are the most common symbols we found. Western tribes used petroglyphs to communicate for thousands of years and so we found them in many places. When my sister visited in Albuquerque, NM, we joined a small crowd of wonder seekers at the Petroglyph National Monument, one of the largest petroglyph sites in North America, and scrambled through volcanic rocks to see hundreds of petroglyphs. In Petrified National Monument, we waited our turn to look through a tower view (that’s what they call stationary binoculars) at the 650 petroglyphs covering Newspaper Rock. We searched for petroglyphs in more remote places too, like at the end of a canyon hike in Hovenweep National Monument in Utah. In Idaho, we climbed a small, steep mountain and then hiked into a canyon behind it to find them etched against the back rocks. And most recently we passed a series of petroglyphs on a hike in the Mojave Desert. We’ve seen a variety of faces, animals, hands, and most commonly circles. Sometimes the circular shapes are spirals and sometimes simply round. Some represent the sun, other’s community, and many representations are unknown. What is clear to me after seeing so many is that humans have found significance in this shape since time immemorial.

In the King Clone Creosote, it’s circular shape saved this ancient plant from obscurity or even worse, destruction. I was researching creosote bushes for my January blog post, Learning a New Language and made an exciting discovery. My favorite desert bush, the tenacious creosote, is also the oldest living thing on the planet. In the early 1970’s, University of California professor, Dr. Frank Vasek and his colleagues discovered through aerial photos some circular patterned creosote bushes. Intrigued by this anomaly, they headed out to the desert to investigate. They found rings, from a few feet to the largest 22 x 8 meters. As they studied these creosote rings, they discovered that, when in a circular formation, they are actually a single organism. Even more incredible, when they determined the age, they discovered that these unusual clones were, depending on size, anywhere from 9,000 to 12,000 years old. This made the largest clone, the King Clone Creosote, the oldest living thing on earth. Older than the Aspens you’ve read about or any other living thing. No matter how you look at it, 12,000 years is a long time.

Yet it still lives in relative obscurity. The Nature Conservancy bought up about seventeen acres to protect the creosote rings, especially the King Clone, from development and off-roading, but beyond that, nothing has been erected to honor this tenacious life.

The gate is gone and tire tracks are entering the preserve

So Dwayne and I paused for a couple days just outside the Mojave National Preserve in order to take the pilgrimage to see the King Clone Creosote. When we pulled onto the dirt road, I was shocked at the off-road vehicle traffic all around the fenced conservancy area. Someone had cut the fence so that off-road vehicles could move unimpeded through this protected area. I jumped out of the truck, horrified by tire tracks everywhere. Fearing that the King Creosote may have been damaged, I panicked and started walking a little frantically around the area looking blindly for a giant ring. Then Dwayne called me back to the truck. He was able to pinpoint the creosote ring, the same way the earlier scientists discovered it, by aerial view, this time with Google Maps. We drove further down the road until we were parallel to the king of all creosote bushes. From there it was easy to find. Fortunately, no vehicles had driven in this area.

The King Clone Creosote spread out beautiful and undisturbed in the middle of this obscure preserve. I was struck at how this precious 12,000 year old organism was protected from the ATV’s only by a flimsy fence, and yet here it was still thriving.

As a way to honor it, I circumambulated it clockwise, as I had learned to do in Nepal around temples and stupas. I took in this shorter than average creosote bush and its dry, brittle-looking evergreen leaves. I know from my research that the creosote bush is the most drought-tolerant plant in the American desert and can live for at least two years with no water at all, so though it looked very dry, it was healthy enough. What struck me was how ordinary it looked. It had none of the majesty of, say, enormous redwoods that are far younger than this bush—at their oldest redwoods are 2,000 years old. Then again the King Clone Creosote’s modesty may be part of its allure. If not for the fact that this clone is preserved in the shape of a ring, we never would have known about it. It certainly would not have caught the scientists’ attention and may have remained undetected and unprotected, possibly lost under an ATV wheel. As I walked reverently to this plant’s empty, sandy center, I reminded myself that I was surrounded by life older than any other. In this space, I recorded a meditation that I will link here when I put it on Insight timer.

In the Imperial Sand Dunes, campers circle their trailers at the base of the dunes. The Imperial Sand Dunes are some of the largest dunes in the US, and many people camp at the entrance. We drove by them often as we traveled between Yuma and Holtville for supplies. Each time I’d point out the communities of trailers and declare, “circle the wagons.” For these configurations of trailers reminded me of the wagons of migrants heading west in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I had learned that the wagons camped in a circle for protection from the indigenous people who were—rightly so when you look at their history after we arrived—not so keen on these intruders. These days the only protection the circle afforded was from the often intense wind. But looking at the trailers at the base of the dunes I realized that protection wasn’t the only reason they clustered together. All activity takes place in the center. Drinking beers and laughing, campers congregate in chairs also placed in circles. Community thrives at the center.

In the boondocking community, circles are often unseen but just as strong. Dwayne and I stayed on BLM land in Holtville, California for the month of January. A hot spring was lightly maintained by the community of boon-dockers who cleaned it every Tuesday morning and who tried to enforce the “no soap, no pets rule” with hand made signs and warnings to anyone who tried to use the place to bathe or bring their dogs. After a while Dwayne and I were on first name basis with some of the regulars. Linda, a Canadian in her late 70’s who has spent every winter here for the last ten years would steer anyone interested in a wash to fill their bucket and walk over to a makeshift shower area in the creosote bushes at the edge of the hot spring grove. Someone had built a little deck from wooden pallets and placed some old tiles beneath it. Charlie and Holden both cared for the hot spring and were the two to wrangle up volunteers to help with the Tuesday morning cleaning, and who kept the old pressure washer working. Two women, both with long silver hair and strong athletic bodies whose names I never knew, were always in the same corner, water-bottles in hand engrossed in each other’s long meandering stories. I enjoyed listening in and out of their adventures, such as the one where one broke her leg while out by herself ocean kayaking in Mexico. A family helped her get to safety and also sat her down for the evening meal.

And then there were the folks who didn’t stay on the BLM land, but passed through. They carried stories of conspiracies, spirituality seeking, books they’ve read, better ways to run the government, and everything else under the sun. If we wished, Dwayne and I were always sure to engage someone in interesting conversation.

After we’d been there for a couple weeks, Dwayne and I saw a duck swimming in one of the hot tubs one morning. “How did that get in here?” I asked Dwayne as I walked over to where the duck was splashing around in the furthest pool. Just then a tiny, sinewy woman leapt from an adjoining pool, plucked the duck from the water, and shoved it under her arm. She stomped at me, shouting at me to leave her duck alone, before moving back into her tub with the duck still under her arm. Startled, I looked around to see if anyone noticed what was going on. She was clearly breaking the rules, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to mess with her.

“She’s not okay,” one of the athletically built storytellers said to me. “A man got really angry that she had a duck in here. I mean I didn’t like it, but the duck was cute and didn’t seem to be bothering anyone, so I just ignored it. But the man here got really furious. And then the woman started screaming. I thought she was going to hit him. So I talked to the man, and that couple is talking to the woman with the duck.”

“What happened to the man,” I asked as I settled into the steaming water next to her.

“I calmed him down and then he decided to leave. He couldn’t stay here with the duck. I get it. I felt bad for him, so I walked him back to his car.”

I looked over at the woman with the duck. She glared back at me and shook her fist. I glanced away.

“Is she alright mentally?,” I asked.

“Probably not,” the woman said with a shrug, “But they’re trying to calm her down.” The woman motioned her head toward the couple, a man and woman I hadn’t seen before, sitting on either side of duck woman. As duck woman shouted they nodded their heads, and talked to her gently. Eventually, she quieted down and started to cry. The woman in the couple patted duck woman’s shoulder. Then when duck woman finished crying, she nodded her head and the couple helped her gather her things and the duck.

Duck woman spun back one more time to swear at me, “Don’t touch my fucking duck.” The couple both looked pointedly at me, and I understood what they wanted me to do. Stay out of it. So I lowered my eyes, and that seemed to satisfy duck woman enough to allow the couple to walk her and her duck out of the gate. They didn’t come back and I wondered if they drove her someplace. Did she have a home?

“Why was she mad at me?” I asked the beautiful long-haired friend.

“Well, you looked at her duck,” she said as if that were reason enough. “I hope she’s okay. I hope the man is too.”

Something rose in me—an unknown feeling I’d had since coming to this community of proximity to free camping land and a hot spring, found voice. They saw one another as members, even if you came for a moment breaking all the rules with your duck and your laundry. Even if you lost your shit at the rule breakers. Even if you looked the wrong way at the duck, you belonged. Someone came forward to offer you care. Even Charlie, one of the keepers of the hot spring, didn’t seem to be bothered when we told him of the incident later.

“Oh yeah, she comes by a couple times a month. Not much we can do about it. I guess she figures that a duck in the desert needs a place to swim once in a while.”

Communities are strong in the same way circles are strong: stress is distributed equally along the arc. Alone we carry all the weight, but when we lean into one another, we thrive. Just as the points on a circle are infinite, so are the possibilities of our community. Just as these strangers came together to help a woman with a duck and a man enraged, so can all communities. If we decide that there is no us or them, there is only us.

As I’m beginning to expand my definition of community, I’m also deepening my understanding of its gift. In psychology, circles represent wholeness, a natural sense of completion. Think about that, if our first impulse with each other, with our environment, with everything that is alive around us were to be in community, I believe together we could heal this fractured world we live in. We could reclaim our wholeness. Perhaps that is the lost message in the petroglyphs. Alone we are incomplete. Perhaps that is the reason for the longevity of the ancient King Clone, or the comfort in the circle of trailers. We need each other. We need to come together not apart when times are hard—especially when times are hard. It only took a duck in the desert for me to get it.